On March 30th, 1968, Lyndon Baines Johnson, the President of the United States, spoke to the nation about the war in Vietnam, as he had so many times before during the months and years defined by the conflict.

If once Lyndon Johnson had spent his presidency passing legislation that tore down the racial segregation of the American South, or sought to lift millions of citizens out of poverty, his presidency had by now become utterly consumed by the war in the former French colony. The man who had bent the American Congress to his will as few presidents ever had now seemed exhausted and cowed by his inability to do the same with the Vietcong— and with his own country, which despite once hailing him as a great statesman, a worthy heir to Franklin Roosevelt and John Kennedy, now in parts hated and resented him.

And still, the end of Johnson’s speech would come as a shock to his countrymen. Restating his intention to seek a negotiated peace and deeming that such an undertaking demanded the full energy and attention of the president, Lyndon Johnson—who had sought and desired power his entire life, and who had loved and cherished the ability to hold this office—would then say words which marked the end of an entire epoch of American history:

"I shall not seek, and will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your President."

With these words, the last of the true liberal titans would exit the stage. After a disappointing showing in the New Hampshire primary that year, Johnson deemed it impossible to mount a successful primary campaign while also bringing the war in Vietnam to a close. The liberal consensus which had birthed the great legislative accomplishments of Johnson’s presidency would perish, and its former supporters would become increasingly dispirited and disillusioned—largely due to the war that Johnson had led his country into.

Over the next decade, conservatives would increasingly seize the initiative, dominating the politics and ideological landscape of the country. But it wasn’t just that conservatives were in power—the long period during which they held the initiative completely changed liberalism. This period of setbacks would shift the psychology, ideology, and sociological base of liberalism to the point where it would become almost unrecognizable to the man who had just announced his intention to leave the presidency.

The Whole World Is Watching

Once Lyndon Johnson had taken himself out of consideration for the presidency, the favorite became immediately apparent: the brother of the man whose assassination had led to Johnson’s own ascent—Robert Kennedy. A man with a strong and mutual grudge against the current occupant, he seemed easily able to rival his dead brother when it came to political ability. Bobby Kennedy appeared to be the right person to lead his country out of the war, but in that same year, he—like his brother before him—would be cut down by an assassin’s bullet.

If the Vietnam War, race riots, and galloping inflation had already robbed liberalism of much of its optimism, the death of the other Kennedy sent it into utter despair. With his death, any hope of restoring the idealism many associated with Camelot was forever lost.

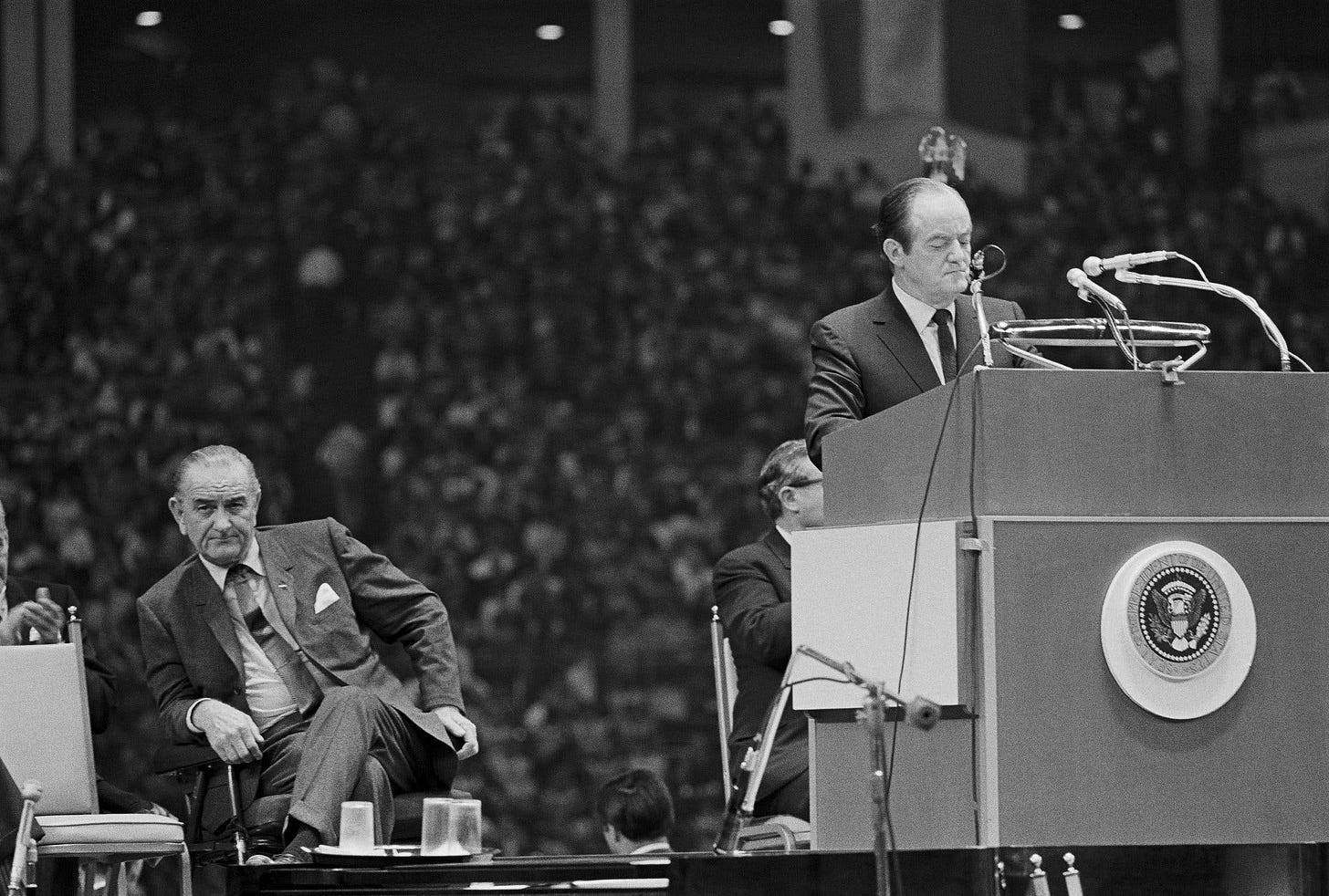

Instead of another charismatic Kennedy, the Democratic nominee for president would be Hubert Humphrey—Lyndon Johnson’s vice president—who lacked Johnson’s titanic stature despite his long-standing advocacy for various liberal causes, including civil rights. This anointment of Humphrey as the standard-bearer of liberal America against the dreaded Richard Nixon is what sent many young activists over the edge. Desiring a clear break from the Johnson administration on the issue of Vietnam, they saw in Humphrey only continuity.

And so, the 1968 Democratic convention descended into chaos, sparking riots and playing directly into the hands of the man who had long run on a platform of law and order. But Nixon would go far beyond merely exploiting existing weaknesses—he would actively intervene to ensure they remained. Tipped off by a former academic and aspiring Washington power player, Henry Kissinger, Nixon would sabotage the peace talks Johnson was engaged in, ensuring that the war would still be ongoing by the time of the November election. This put Humphrey in a difficult position, as his electorate desired nothing more than a break from the president’s policy on Vietnam. Johnson, however, heavily pressured Humphrey to continue toeing the White House line.

In spite of all these difficulties—or perhaps because of them—Humphrey put up an incredible fight. Starting more than ten points behind Nixon, he slowly but surely narrowed the gap as the campaign progressed. Had a ceasefire in Vietnam been announced before the election, he likely would have won. In the final weeks of the campaign, the vice president broke from the White House and called for a bombing halt in Vietnam.

Humphrey would follow closely in Nixon’s footsteps—failing to win the presidency as vice president, and being beaten in a close election.

The events of that year would mark the liberal psyche for years to come, the closeness of the election, the chaos and confusion of the riots which had engulfed the Democratic convention and the utter dreadfulness of the Nixon administration creating a permanent trauma.

What would reshape liberalism even more is the utter horror that was the Nixon presidency. A man just as versed in the dirty elements of politics as Lyndon Johnson was, he proved to abuse his office in a way that few Presidents before or after would. If the Johnson administration with its lies around the war in Vietnam had begun the process of disilusioning the American people from the vision of the American Presidency embodied in Camelot, Nixon would utterly destroy what little trust they had left. This disilusionment should have been ample opportunity for Democrats to regain momentum and perhaps the Presidency, but instead they would run into one of the biggest failures in their history.

I Believe Him

After the chaos of the 1968 convention, Democrats sought to address the concerns of their base and limit the power of party grandees. The McGovern Commission drastically changed the way the Democratic Party would choose its nominee, placing power almost entirely in the hands of the primary electorate. This new system handed the nomination to a relative outsider: South Dakota Senator George McGovern. Unpopular with the established leaders of the Democratic Party, though Lyndon Johnson at this point the only still living Democratic President would begrudingly endorse him, McGovern managed to win over the Democratic base with the help of thousands of student activists, including a young Rhodes scholar from Arkansas and his politically engaged girlfriend studying at yale law.

But this outsider appeal would be of little use to McGovern when it came to persuading the general electorate. His 1972 campaign became a generational disaster, with Nixon once more resorting to the dirty tricks that had already succeeded in neutralizing the "October surprise" Lyndon Johnson had once prepared for him. McGovern struggled with his vice presidential pick—removing him from the ticket after his medical history became public—faced backlash over his promise to grant amnesty to draft dodgers, and ran a generally amateurish and poorly organized campaign. In the end, Nixon won 49 states, 520 electoral votes, 60 percent of the popular vote and the largest landslide in 100 years.

With this victory, Nixon had truly ended any hope of restoring the liberal status quo. When he claimed to speak for the “silent majority,” his assertion could no longer simply be dismissed. Not even his resignation in disgrace less than two years later would change that.

The Long March Through the Institutions

If the trauma of Nixon’s election victory and Presidency had shifted the liberal psyche the circumstances of his downfall would transform it further. That was because Nixon hadn’t been undone by the voters; instead, two largely unknown investigative journalists accomplished what the Democrats could not—bringing down the man who, more than anyone, had benefited from the collapse of liberal dominance. The findings of woodward and Bernstein were further compiled into a damaging report by the House Judiciary Comitee, which included the Rhodes scholars girlfriend and now Yale Law graduate. Republicans in Congress would deliver the final blow when they signaled they would join their Democratic colleagues in advancing impeachment proceedings. This shifted the perception of political power among many liberals, rather than through the ballot box Nixon had been undone by the “institutions”. Bill and Hillary Clinton wouldn’t contribute to the dreaded President’s downfall through their engagment in a political campaign, but through Hillary’s work as an intern and Capitol Hill staffer. If Liberalism was seeing setbacks in actual elections it could triumph through journalism, volunteer work, advocacy orginisations and the courts; with the biggest actual policy triumphs of liberalism in this era coming in the Roe v Wade ruling of the US Supreme Court which saw a right to an abortion guarantued in the constitutional right to privacy. This ability to influence policy through the institutions would persuade many of the students who had previously thrown chairs and molotov cocktails at policemen, after seeing their hopes of political revolution dashed, to complete their degrees while holding on to their radical beliefs. This created a new class of often college educated and relativly educated leftists and liberals who sought to change the world around them not through mass political movements but rather thorugh “the long march through the institution”.

Despite this shift in liberal political engagment Gerald Ford the man who followed Richard Nixon into the Presidency wouldn’t be able to regain much momentum, hobbled from the beginning of his presidency by the unpopular decision to pardon his predecessor. He was further hamstrung by the fall of South Vietnam, with the chaotic evacuation of the American embassy serving as a perfect symbol of the United States' humiliation at the hands of the Vietnamese. The concept of “peace with honor” now sounded utterly ridiculous.

This should have put Democrats in a strong position to regain the initiative, with Republicans just as divided and adrift as they had been in 1968. Ford would even face a primary challenge from a darling of the right and former actor. And while the Republican convention did not erupt into riots, the strong showing by the former California governor perfectly illustrated President Ford’s weakness.

The stage was set for a new Democratic leader to restore the party to its former glory and thoroughly trounce the weak and divided Republicans.

Jimmy Carter would not rise to the occasion.

A Crisis of Confidence

Jimmy Carter, despite being personally liked and respected by many, turned what should have been a period of Democratic dominance into an exhausting slog. Running for president after Watergate, the fall of Saigon, and a debate in which his opponent bizarrely disputed the Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe, he won a rather marginal victory—far from the landslide it should have been.

During his presidency, he struggled to pass significant legislation through Congress, despite Democrats holding their first trifecta since 1968. Ultimately, he was undone by foreign policy crises, which contributed to the high inflation that had bedeviled the United States for what was, at this point, an entire decade.

But the issues facing the left were no longer confined to the United States alone. The same high inflation that plagued the U.S. also led to escalating social strife in the United Kingdom, becoming a major problem for Labour Prime Minister James Callaghan. High inflation necessitated high interest rates, which hurt industry and led to a wave of strikes—alienating liberals and socialists from their traditional labor constituency.

The persistent economic crisis also contributed to a shifting intellectual environment in economics. Faith in the state was weakening, and there was a growing push for renewed competitiveness through deregulation and the rollback of government power. Carter, after initially resisting this new consensus, would ultimately embrace it—deregulating the trucking, airline, and telecommunications sectors in his final years as president.

But despite Carter starting the United States on its road toward renewed faith in the free market, he would not be the president most associated with this development. Instead, a new kind of conservative would emerge in both the U.S. and the United Kingdom—one much more drastic in its desire to roll back state power than their predecessors ever were. This kind of conservative would prove an even more formidable challenge to liberalism than Nixon ever had.

Continued in Part II